Some weeks ago, this blog reported the first appearance online of a major legal-history manuscript in Rome, the

Tractatus Vaticanus or

Vat.lat.1352. At that time the images of it were only offered in black and white, and at poor resolution. Now this fine old codex is available in color and at excellent resolution as the work of digitization proceeds.

The core material in this book is the so-called

Quadripartitus, a

monument of Carolingian canon law, which is a guide to penances at

confession that is not in itself rare. In all, 11 manuscripts survive (this one is

siglum Y, see

Wikipedia and

Rob Meens for a survey of these manuscripts). Its organization is as follows: Fols

12 - 84r: Paenitentiale. Fols 84v - 97r: more sections "ex panitentiali

romano," "ex penitentiali theodori" etc, including several

excerpta patrum (see

Oberleitner, Augustinus, 1970).

Its particular interest however lies in its occasional

excerpta (quotations) from lawyers and church fathers, some unique, about jurisprudence. The page of greatest interest is fol. 62r which shows a very early

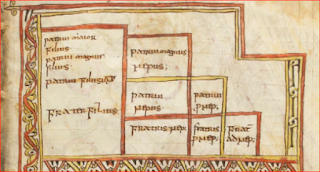

arbor juris diagram:

Readers of the

earlier blog post, may recall that the text beneath the diagram refers to it as

both an

arbor and as a

scala. This diagram is canonical to a key topic in Roman private law: inheritance. It explains which relations are entitled and in which order when someone dies intestate and leaving property.

A case can be made that arbor is the medieval term whereas scala is the older Latin technical term for this monument in the history of visualization. In the classification of these diagrams by Hermann Schadt (see my

Missing Manual), this form belongs to the Typ 1 class.

Schadt argued that such diagrams may not just have been devised in late antiquity, but that they could indeed have already existed in the classical Roman period. Since Schadt's important book in German,

Die Darstellungen der Arbores Consanguinitatis und der Arbores Affinitatis: Bildschemata in juristischen Handschriften (Tübingen: Wasmuth, 1982) is not easily accessible to most readers, I will set out his case in summary here.

Schadt’s first argument is one of usage. It is hardly plausible to suppose that the emperor Justinian’s

Institutions, a foundational law textbook issued in 533 CE, introduced this diagram type to legal scholarship for the first time, since the

Institutions are based on previous textbooks and explain the

degrees of relationship to the student without any especial introduction of the topic. Under the supervision of

Tribonian,

two law professors (Theophilus and Dorotheus) had been assigned to extract

statements about the basic institutions ("Institutiones") of Roman law

from the existing teaching books.

One infers from this procedure that visualization of the degrees by means of a diagram was not new, but already an established skill among law teachers. Schadt notes that Servius (4th century) quotes Varro (1st century) as having written on the topic of degrees, adding that another work on the topic is attributed to Ulpian (+277), though no diagram is mentioned by these. But the word degree is telling.

Schadt stresses that the

Pauli Sententiae (about 400) alludes to a diagram of the

arbor juris type.

At this point in the argument, he refers to

Vat. lat.1352 and suggests that its medieval repetition of the word

scala (ladder) may well be quoting some centuries-old legal tract.

Schadt’s second argument is one of inertia: the arrangement of such a diagram would have been difficult to design and therefore it is likely to have been conserved unchanged once it entered wide use (and not to have been altered by Tribonian or any compiler).

His third argument is chronological, alluding to the antiquarian content of the oldest form of Typ 1 tables which have textual tags saying they represent the “lex hereditatis”, the law of succession prior to the Roman Republican period. Those diagrams contain only the

adgnati, that is to say those relations under the

potestas or

manus of the head of the Roman household who comprised the

sui heredes – both the younger family living at home including the wives (the

uxor in manu, the

nurus in manu, etc.) and the older relatives living elsewhere, the

proximi adgnati, essentially the head of the household’s cousins, since the older generations are dead.

The diagrams thus sets out the legal bounds of family under the fifth-century-BCE

Law of the Twelve Tables and gives no acknowledgement to the praetorian legislation of the Republican period, which widened the circle of entitled family to the cognate relatives. (It should be noted however that cognates were only entitled to

bonorum possessio, not to full title in intestate property, and that they therefore had only secondary status to those who claimed under the civil-law provisions.)

In addition, this table does not affirm the right of a child to inherit from an intestate mother, which was introduced by the

Senatus Consultum Tertullianum under Hadrian (117-138). The ego’s sister is also missing from the diagram, though Gaius 2.85 states that she was considered agnate in his day.

Schadt's fourth argument is linguistic: some of the terminology (

patruus maior and

maximus) is antiquated and would not have been employed by a late-antique lawyer. Typ 1 should therefore be dated before the mid second century, he suggests, citing Max Kaser,

Das Römische Privatrecht II, 141, 336.

His fifth argument is based on the diagram’s later evolution: If a more “advanced” scala (a left-right-mirrored version of Typ 5, the whole cognate family, extended to the 8th degree) was drawn in the

Notitia Dignitatum (circa 400 CE), then a simpler version, the agnate-family Typ 1, must date from earlier, perhaps a lot earlier.

Schadt thus argues the diagram was treated as a scala (ladder) in antiquity, and that the

Baumvorstellung notion for it did not arise until the 7th or 8th century (

Darstellungen, p 59), and that the basic arbor juris diagram goes further than the late-antique period.

The four main manuscripts transmitting this "classical" Typ 1 scala, each with its own defects, are:

Paris, lat. 4410, fol. 3v, also often called the

Stemma de Cujas (image on

Mandragore):

Paris, lat. 4412, fol 75v-76r

Vatican,

Reg. lat. 1023, 66v-67r (only online in black and white so far)

Leiden, BPL 114, fol 8r,

(image on Socrates).

A mere glance at the five items above will make plain that none is definitive. The Tractatus has a version where cognate relatives are mentioned too, though this was not valid in early Roman law. The first column of the Stemma of Cujas (Cuiacus) has slipped lower by one row. Reg.lat.1023 is a dog's breakfast of graphic alterations and lat.4412 and BPL 114 are simply ill-assembled. The version in my missing manual is the sum of this design, eliminating the errors.

There are also said to be other manuscripts with similar figures in existence, as cited by Max Conrat,

Geschichte,

page 145, note 2 (Schadt does not discuss these), but I have not been able to confirm these exist, since none of them is, as far as I can see, yet accessible online. Those citations are of an

Epitome ab Aegidio Edita (Cod. Lugd. 169 =

BPL 169 at Leiden, only 4 images digitized) and a breviary of law, Paris, BNF latin 4406, variously given as fols. 57, 58 or 68 (not digitized yet by Gallica

that far through the book). Conrat's Lugd. 47, another breviary, listed as Lugd. Bat. 47 in

Haenel, is probably

VLQ 47 at Leiden, but only 8 images of this are offered on

Socrates.