The BAV library has made no announcement. I am breaking the news here on the world's only portal that monitors their largely unnoticed digital program.

There can be no doubt the documents are genuine and date from 1527-28. Here is Henry's sign-off: "Written with the hand of him [which desireth as much to be yours as you do to have him], H. AB R."

How they got to Rome is anyone's guess (perhaps stolen by a Boleyn confidant, probably taken via France, since French notes are attached). For centuries, Vatican librarians have been showing them to impress high-ranking English visitors to Rome. Now at last, the rest of us can be titillated too.

The reference to "pretty dukkys" in the screenshot above from folio 15 employs dug, the conventional 16th-century English word for a woman's breast. The whole sentence has Henry "wishing myself (especially an evening) in my sweetheart’s arms, whose pretty dukkys I trust shortly to kiss."

Devious Henry ends another letter: "No more to you at this present, mine own darling, for lack of time, but that I would you were in mine arms, or I in yours, for I think it long since I kissed you" (From Letter 16 as transcribed on The Anne Boleyn Files, which also has a debate about demanding their return to England.)

The story of Henry's seduction ended, as we know, badly. Henry divorced, wed Anne, but dumped her and had her beheaded at the Tower of London in 1536.

My unofficial list (the only list, since the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana issues none) of all 32 digitizations on March 15 follows. I will add more details as I have time:

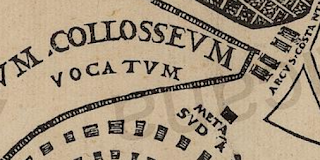

- Barb.lat.4432, Leonardo Bufalini's 1551 map of Rome, the first ever printed. None of the first printing survives and only three copies of the second printing (two at Vatican, one at British Library). This one is bound with an 1880 monograph describing it. Here is the Colosseum and Meta Sudans as they then were:

- Borg.arm.65, with this wonderful Armenian angel:

- Cappon.307, monumental inscriptions, many Greek

- Reg.lat.26, illuminated bible in Old French, 13th or 14th century. Here is Jonah being swallowed by the whale on fol. 178r (the silver has turned black):

- Urb.lat.90, Bernard of Clairvaux, Renaissance manuscript

- Urb.lat.219, Seneca, Letters, 15th C

- Urb.lat.245, Pliny the Younger, Natural History, manuscript dated 1440

- Urb.lat.265, Vitello, Optica, 14th century, with many diagrams like this at fol. 19r

- Urb.lat.316, Cicero, Letters, 1453

- Urb.lat.322, Cicero, Letters, 15th century

- Urb.lat.335, Quintilian, Speeches, 15th century

- Urb.lat.385, Rufinus Latin of Eusebius, History of the Church

- Urb.lat.405, Piccolomini's history of Frederick III, 15th century

- Urb.lat.488, Origen of Alexandria in Rufinus translation

- Urb.lat.490, Urban of Urbanus, commentary

- Urb.lat.499, Nicolò di Vito Gozzi

- Urb.lat.504, On Zeno of Verona, plus section by Basil the Great

- Urb.lat.511, Bartholomew of San Concordio, moral treatise with alphabetical list of conscience issues

- Urb.lat.534, Antony de Sancto Leone

- Urb.lat.543, Canticles, glossed

- Vat.ebr.530.pt.1, collection of unbound fragments and quires from various manuscripts and books, including what seems to be a 17th-century textbook with a schoolroom picture that depicts two Jewish schoolboys greeting one another with high fives:

- Vat.gr.357, Gospels, Pinakes

- Vat.gr.2365,

- Vat.lat.441, Augustine of Hippo, City of God

- Vat.lat.449, Augustine, On Genesis

- Vat.lat.481, Augustine, On Gospel of John

- Vat.lat.487, Augustine, De consensu evangelistarum

- Vat.lat.550, Leo the Great, Sermons

- Vat.lat.560, Boethius, De Trinitate, etc

- Vat.lat.563, Boethius, Consolations of Philosophy

- Vat.lat.3467, the Count Paschasio Diaz Garion Psalter, a Latin prayer-book from Spanish Naples with illuminations by Matteo Felice, including a fine Virga Jesse as frontispiece: Here are some Judaean kings perched in the tree:

In a full page composite Passion Week illumination, we see Judas hiding his face when the photo is taken at the Last Supper: - Vat.lat.3731.pt.A, Henry VIII's autograph letters to Anne Boleyn with French translations. See also Rome Reborn from an exhibition in Washington. One letter was briefly lent in 2009 to the British Museum.